Lee Marvin is a repeat offender here at Noir City. His steely visage is always a welcome sight, but even Lee had to question what the hell he was doing in a film like Violent Saturday. According to Eddie Muller, Marvin hated the movie, saying his performance made him look like a fool. It's a rather unbelievable statement, especially when you consider that director Richard Fleischer cast Ernest Borgnine as an Amish person. Ernie is saddled with a beard and loads of "thee, thou, thy" dialogue. Thy cup will runneth over with laughter when you get a good look at Borgnine in full gear. As for Marvin, his awesomely garish blue ensemble is more suited for Studio 54 than 1954.

Why, Lee? Why?!

Violent Saturday is two parts caper film and three parts soapy, Peyton Place melodrama. The ever versatile Fleischer not only swings between the two disparate halves with ease, he does it in CinemaScope so the screen contains more soapy suds per square inch than the Academy ratio would allow. We meet the creepy Peeping Tom banker who ogles the pretty young nurse from outside her window as she undresses. We meet the Amish family who offers sanctuary to our hero Victor Mature. We spend time with the criminals played by Marvin, Stephen McNally and hte great J. Carroll Nash. And we bear witness to the lovely Sylvia Sidney, a librarian who has spent way too much time checking out books about petty larceny. Her eventual Meet Cute with the Peeping Pervert is just one of the many crowd-pleasing highlights Violent Saturday has to offer.

Everything and everybody is connected in this small town, and the characters' dramatic interplay is as intricately and convolutedly plotted as the film's central heist. Every kind of sin is explored, countered only by the piousness of that Amish family. When patriarch Ernie B. became an avenging angel for the Lord, we denizens of Noir City understood why this played as part of the Saturday matinee. This is the stuff lazy Saturday afternoons at the cinema are made for; the Castro Theatre crowd sopped it off the screen with a biscuit.

When one thinks of noir, or of capers for that matter, director Federico Fellini doesn't immediately spring to mind, though one could make a strong case for the noirish underpinnings of La Strada. The Italian master lent his screenwriting skils to director Pietro Germi's Four Ways Out, which played the early half of the Saturday night double feature at Noir City. It came to us in a pristine, gorgeous 35mm print whose tactile black and white cinematography highlighted the broad strokes of neorealism peering out from beneath its larcenous storyline. This time, the mark is a soccer stadium's ticket revenue take, crammed in generic-looking suitcases carried by several career criminals and one out-of-his-league teenage boy.

The young man's palpable fear of being caught leads him to make some understable yet very large mistakes that affect the rest of his crew. Though it's never clearly evident why someone so green would be in on this complicated scheme, Germi and Fellini use him as the film's desperate conscience. Though we know Noir City's advertised guarantee is "no happy endings" to its films, Four Ways Out offers a slight bit of respite when it comes to the young man's comeuppance. Fellini gives his final scene an operatic crescendo that would be shameless if it weren't so damn effective.

Poor kid.

Also effective are the performances by Paul Muller as "il professore," the mastermind of the heist, and a young, unforgivably gorgeous Gina Lollobrigida as Daniela, a possibly duplicitous lover whose actions don't bode well for one of the criminals. For Lollobrigida's, and the filmmakers', troubles, Four Ways Out won the Best Italian Film at the 1951 Venice Film Festival. You'll never look at a town square fountain or a building ledge the same way after you see it.

Four Ways Out played on a double bill with Mario Monicelli's excellent, Oscar nominated caper classic Big Deal on Madonna Street. I skipped that one, if only because I'd done three prior movies and a brief stint in the enormous protest march that took up much of Market Street on Saturday. I had a good excuse to drop out of seeing the film, but you don't. Rent it or look for it on TCM.

I was present for The Big Risk, which deserves its own piece later in this series. In the meantime, let's continue with yet another famous director whom people tend to forget was majorly influened by, and contributed to, film noir.

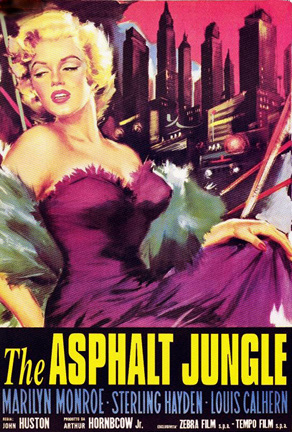

In his introduction to 1956's The Killing, the Czar of Noir told us that Sterling Hayden and director Stanley Kubrick had a major falling out over the film's bouncy, memorable flashback structure. Seems Hayden thought the non-linear nature of the film screwed with his performance. Hayden couldn't have been more wrong, and Kubrick's victory over his then much more powerful lead actor proves it. The film plays as Kubrick and his screenwrier Jim Thompson intended. If you wanted to know where Quentin Tarantino got that awesome idea to fragment the robbery in Jackie Brown into overlapping flashbacks, here is your answer.

Hayden and his cronies knock over a race track on a very profitable day. The heist is complicated, and way too dependent upon a slew of people prone to human error and fits of uncontrollable jealousy. But the crew, and noir master Thompson, pull it off, tying every single loose end into a tightly pulled, ironic noose.

Helping to hang at least one character is Marie Windsor. She's the gorgeous, acid-tongued wife of Noir City stalwart Elisha Cook Jr. Knowing she's at least 6 furlongs out of his league, the nervous Cook will do anything to keep her happy, including telling her private details about Hayden's heist. This is a bad idea; Windsor's been seeing another guy--a favorite to Cook's 100-1 longshot of a husband--and this new horse wants a piece of the action.

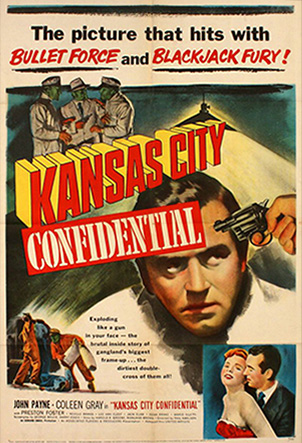

Though she's billed way under the title, Windsor runs off with the picture. Her performance is the kind that wins Supporting Actress Oscars in a more just awards-centric world. Not even Hayden can compete with her. When he rebuffs her advances and tells her to "beat it," he almost seems more wounded than she is at the rejection. She even manages to hold her own in the unforgettable department against her gloriously insane co-star Timothy Carey and Colleen Grey, who plays Windsor's complete opposite. In a film with one of the most memorably complex heists, Windsor's performance commits an even more memorable theft.

(A special shout out to James Edwards, who shares the screen with Carey yet manages to leave a stinging, karmic-filled impression in a very short time.)

Last up is Cruel Gun Story, a 1964 Japanese crime tale starring Jo Shishido, the only male actor to benefit from getting implants. And no, they weren't in his boobs--they were in his face. You get used to his chipmunk-like appearance pretty quickly, however, because this movie is Vi-O-Lent! The climactic, over-the-top shootout, featuring explosions and waves of people being mowed down, evoked the coolness of Michael Mann merged with the gonzo batshit penchant for carnage wielded by Mel Gibson. Though nowhere near as gory as anything Mad Mel threw his camera behind, Cruel Gun Story has Gibson's thesis statement of attempted redemption through violent suffering: Shishido is doing this heist, and all that gunplay, to help his paraplegic sister get a surgery to allow her to walk again. Of course, redemption ain't coming for anybody in Noir City.

The emotional pull is definitely there in director Takumi Furukawa's most notorious picture, but it comes with a heaping side of admittedly delicious nihilism. Everything you need to know about Cruel Gun Story is right there in the title.

Next time: Lino Ventura and a Coen Brothers inspiration.

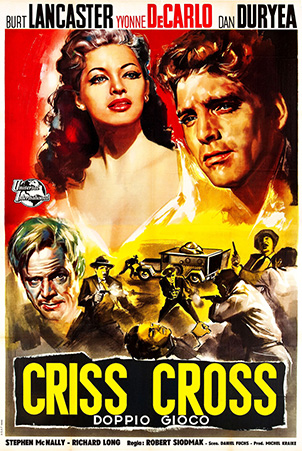

Last dispatch: Criss Cross Will Make Ya Jump Jump!